There’s a chap who always turns up to industry events in London wearing head-to-toe Burberry. Not subtle, curated Burberry—we’re talking full-on, trademark-check-explosion Burberry. We call him the Tartan Terror behind his back, which I feel mildly guilty about, but not guilty enough to stop. He’s the walking embodiment of what happens when your knowledge of British luxury starts and ends with our most famous export. Don’t get me wrong—Burberry deserves its status. But treating it as the beginning and end of British luxury is like claiming you’re a music expert because you own a Beatles album.

The British luxury landscape is far richer and more varied than most realize, even many Brits themselves. We have this odd national habit of underplaying our luxury credentials while simultaneously being home to some of the most skilled artisans and heritage houses in the world. For every globally recognized name like Burberry, there are half a dozen equally impressive but more discreet operations quietly producing extraordinary goods with minimal fanfare. Their relative obscurity isn’t due to inferior quality—quite the opposite. Many maintain a deliberate low profile because true luxury, as the saying goes, whispers rather than shouts.

I’ve spent years exploring these less trumpeted corners of British luxury, partly for work (the perk of being a style journalist is that “research” can mean handling exceptional products and calling it labor) and partly from personal fascination with craftsmanship that has survived the mass production era. What follows isn’t a comprehensive guide—more a personal tour through British luxury brands that deserve more recognition than they currently receive.

Let’s start with leather goods, where Britain has a heritage that rivals anything from Italy or France, though we’re typically more reserved about broadcasting it. Ettinger, a Royal Warrant holder, produces leather accessories that quietly outclass many flashier continental competitors. Their bridle hide wallets develop a patina over years that tells the story of their use—the antithesis of disposable fashion. I’ve had the same Ettinger card holder for nearly eight years, and it’s aged like a fine whisky, developing character lines and a honeyed color that no new item could replicate.

Tanner Krolle is another name that deserves wider recognition. Founded in 1856, they’ve made luggage for everyone from the British royal family to Jackie Onassis without shouting about it. Unlike certain luxury brands that emblazon logos across their products, Tanner Krolle is all about subtle details recognizable only to those who know. Their pieces are serious investments (I’m still saving for one of their weekend bags, which costs roughly the same as a decent used car), but they’re designed to be passed down through generations rather than replaced with next season’s model.

In footwear, we’ve got a lineup that should make Italy nervous. Everyone knows Church’s and Loake, but what about Gaziano & Girling? They’re relatively young by British heritage standards—founded in 2006—but have elevated shoemaking to an art form that combines traditional techniques with more contemporary aesthetics. Their factory in Kettering produces shoes that make footwear enthusiasts go weak at the knees. I once watched a Japanese buyer at Pitti Uomo literally gasp when examining a pair of G&G Adelaide oxfords, which made me feel patriotic in a way that sport never has.

Crockett & Jones deserves more global recognition too. James Bond has worn their shoes in several recent films, which has raised their profile somewhat, but they’re still not mentioned in the same breath as some Italian makers despite comparable quality. Their Skye model, a sturdy brogue derby boot, has taken me through eight London winters without complaint, developing an almost mirror-like patina through nothing more than regular polish and the occasional encounter with horse chestnut trees in Regent’s Park.

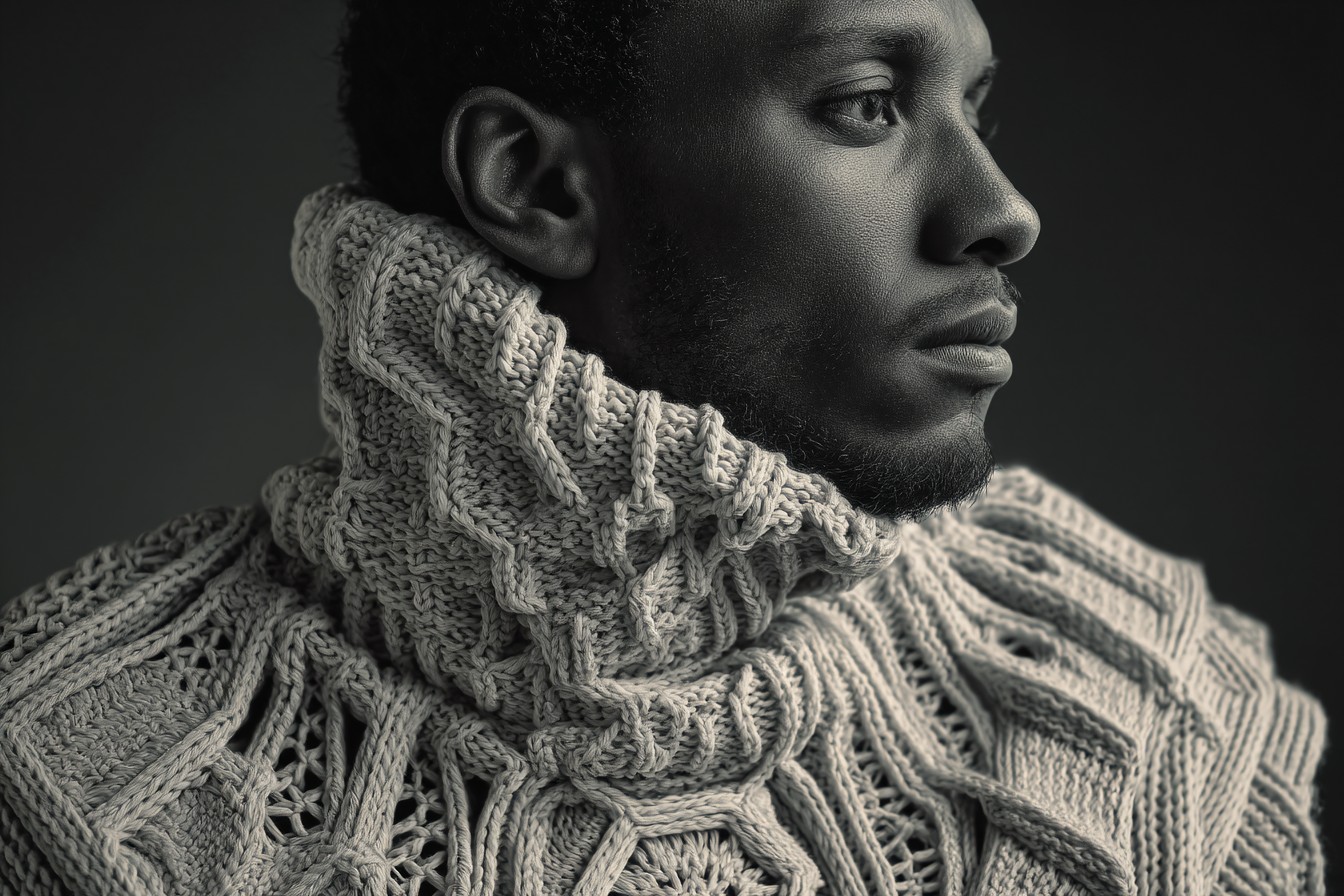

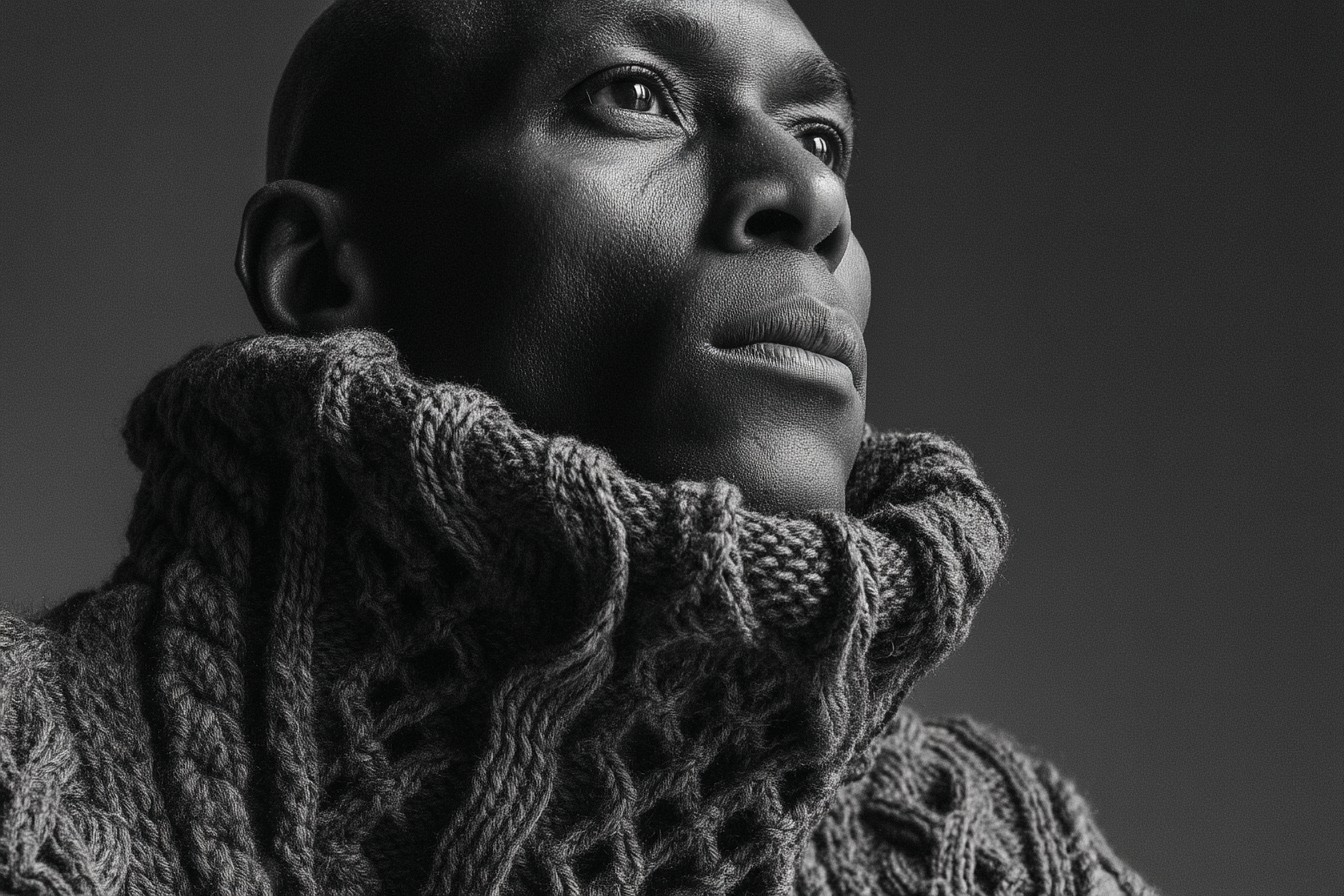

For knitwear, Britain’s offerings extend far beyond the obvious names. Corgi, based in Wales, has been making exceptional knitwear since 1892. Their cashmere is impossibly soft yet robust enough to last for years. What sets them apart is their hand-finishing—the way collars sit, the precision of their patterns, the slight variations that remind you a skilled human made this garment rather than just programming a machine. I have a Corgi cashmere cardigan that’s survived six house moves and countless washing machine cycles while still looking remarkably dignified, which is more than can be said for its owner after similar treatment.

Johnstons of Elgin deserves a special mention for their unique place in the luxury ecosystem. They not only create their own exceptional cashmere pieces but also produce materials for many other high-end brands who, for obvious reasons, don’t advertise this fact. A fashion industry open secret is that some items from famous European luxury houses are made with Johnstons cashmere, though you’ll pay a significant premium for the privilege of a different label. Their own-brand scarves and blankets offer access to this quality at a fraction of the price you’d pay elsewhere, which doesn’t make them cheap, but does make them exceptional value in the true sense of the word.

In tailoring, beyond the obvious Savile Row establishments, there are British companies doing fascinating work. Private White V.C., based in Manchester, has preserved a factory that’s been producing outerwear since 1853. Their pieces combine military-grade functionality with the kind of quiet style that gets you stopped by Japanese street style photographers who recognize quality from fifty paces. Their Ventile cotton outerwear is both historically significant (developed for RAF pilots during WWII) and perfectly adapted to our climate. I have one of their original Twin Track jackets that’s accompanied me through downpours that would defeat lesser garments, all while looking increasingly characterful rather than simply worn out.

Drake’s has evolved from a tie maker to one of Britain’s most well-rounded luxury brands, creating everything from casual clothing to formal accessories with a distinctive point of view that’s neither stuck in tradition nor chasing trends. Their slightly relaxed take on classic menswear makes tradition feel relevant rather than restrictive. I’ve got a navy Drake’s blazer with just enough structure to look proper but enough give to feel comfortable after a long lunch—the sartorial equivalent of having your cake and eating it too.

For those with seriously deep pockets, Thom Sweeney offers bespoke and ready-to-wear clothing that rivals anything from Italy but with a distinctly British sensibility—structured but not stiff, elegant but not showy. They represent the new guard of British tailoring that respects tradition without being imprisoned by it. I haven’t been able to justify their bespoke offering yet, but their ready-to-wear suits have a cut that somehow makes me look like I’ve spent more time at the gym than I actually have, which is perhaps the highest compliment one can pay a tailor.

In accessories, Sheaffer Blue creates umbrellas that transform a necessity in our climate into an object of desire. Handmade in England using materials like chestnut wood and waxed cotton, they’re designed to be repairing rather than replacing when damaged. In a world of disposable £5 umbrellas left broken in bins during the first substantial wind, there’s something deeply satisfying about carrying one that’s built to last decades. I was gifted one for my thirty-fifth birthday, and it’s the only umbrella I’ve ever actively tried not to lose.

British watchmaking is experiencing a renaissance that few people outside the horological community have noticed. Bremont has led the charge, creating mechanical watches that combine serious technical credentials with distinctly British design sensibilities. They’re not cheap, but compared to Swiss watches of similar quality, they offer remarkable value. Their aviation heritage provides genuine character rather than the manufactured stories some luxury brands rely on. I handled their ALT1-C model at their Mayfair boutique recently and nearly convinced myself that remortgaging for a watch was a perfectly reasonable life choice.

If Bremont is slightly beyond your reach (as it remains beyond mine for now), AnOrdain offers something unique at a more accessible price point. Based in Glasgow, they create watches with vitreous enamel dials made using traditional techniques that are nearly extinct. Each dial takes days to produce, with a failure rate that would drive most businesses mad, resulting in depths of color that can’t be achieved by more conventional methods. There’s something wonderfully obsessive about their approach that feels quintessentially British—pursuing perfection not because the market demands it, but because anything less would offend their sensibilities.

In the realm of small leather goods and accessories, Pickett offers quiet luxury for those who know. Their colors are extraordinary—subtle but distinctive, classic but never boring. Their leather-bound journals and photo frames elevate gift-giving beyond the obvious choices. I have one of their card cases in olive green that has prompted more “where did you get that?” questions than items costing many times more.

For those interested in British luxury that extends beyond the closet, Linley creates furniture and home accessories that demonstrate what happens when exceptional materials meet genuine design vision. Founded by David Linley (nephew of Queen Elizabeth II), the company creates pieces that will become tomorrow’s antiques—modern in design but classical in execution and quality. I can’t afford their furniture yet, but one of their walnut document boxes sits on my desk as daily inspiration to write enough words to eventually justify a matching desk.

The common thread running through all these brands is a commitment to substance over show. British luxury at its best embodies the same qualities as the ideal English gentleman (a somewhat outdated concept, I know, but bear with me)—well-made, reliable, elegant without being flashy, improving with age, and possessing hidden depths that reveal themselves only with time and attention.

What most of these brands lack isn’t quality but the marketing muscle of the major luxury conglomerates. They don’t have the budgets for celebrities, fashion show spectaculars, or airport billboards. What they offer instead is something increasingly rare—products made to standards determined by pride and tradition rather than quarterly profit reports. Many remain independently owned, making decisions based on quality rather than shareholder returns.

That’s not to romanticize them as charity operations—they’re businesses that need to make money. But there’s a fundamentally different approach when a brand measures success in generations rather than financial quarters. It shows in details most people won’t consciously notice but will instinctively appreciate: the weight of a perfect brass zipper, the way a collar sits against your neck, the precise shade of burgundy that’s neither too purple nor too brown.

So the next time you’re considering an investment in luxury, perhaps look beyond the obvious global names to these quieter British alternatives. They may not provide the immediate status recognition of more famous logos, but they offer something more valuable—genuine quality, distinctive character, and the quiet satisfaction of knowing you’ve chosen substance over spectacle. Just don’t become the Tartan Terror’s counterpart—the person so obsessed with obscure British luxury that no one can have a normal conversation with you about clothes ever again. Even I have limits, and I write about this stuff for a living.