My grandmother was a knitter. Not one of those casual, pick-it-up-for-a-week-then-abandon-it types, but a proper, dedicated craftswoman who could create a Fair Isle masterpiece while simultaneously watching Coronation Street and telling my grandfather where he’d left his glasses (invariably on top of his head). Her knitting needles moved with the hypnotic rhythm of industrial machinery, the soft click-click-click forming a soundtrack to my childhood winters.

When I was about eleven, she handed me a navy blue jumper she’d just finished. “This’ll last you,” she said with typical Yorkshire understatement. I didn’t fully appreciate what she meant until decades later, when I found that same jumper in a box while moving flats. Still perfectly wearable, still holding its shape, the wool as resilient as the day she’d cast off the final stitch. That jumper had outlasted relationships, fashion trends, and several iterations of my own identity. It was then I realized what proper knitwear actually means—not just something warm, but something that endures, something made with skill and appropriate materials that defies our disposable culture.

I mention this because it’s impossible for me to consider British knitwear without acknowledging its roots in that tradition of domestic craftsmanship. The industrial revolution mechanized the process, but the principles remained the same: using quality yarns, proper techniques, and an understanding of how garments should fit and function in our challenging climate. Those values still distinguish the best British knitwear makers today, even as so much manufacturing has been outsourced to cheaper locations using inferior materials.

Let’s be honest—proper knitwear isn’t cheap. If you’ve been conditioned by high street prices, the cost of traditionally made British jumpers might initially seem outrageous. But here’s where some basic mathematics comes in handy. That £30 acrylic blend jumper from a fast fashion retailer might last a season before pilling, stretching, or generally looking sad. A £300 jumper from a quality British maker could easily last 15+ years with minimal care. That’s £20 per year versus £30 for a single season—suddenly the “expensive” option reveals itself as the economical one.

The Scottish borders remain the epicenter of quality British knitwear production. Hawick, in particular, is to jumpers what Northampton is to shoes—a place where the skills and infrastructure for exceptional manufacturing have been maintained despite every economic incentive to abandon them. Brands like William Lockie have been producing knitwear here since 1874, using techniques and maintaining standards that have changed remarkably little in the intervening century and a half.

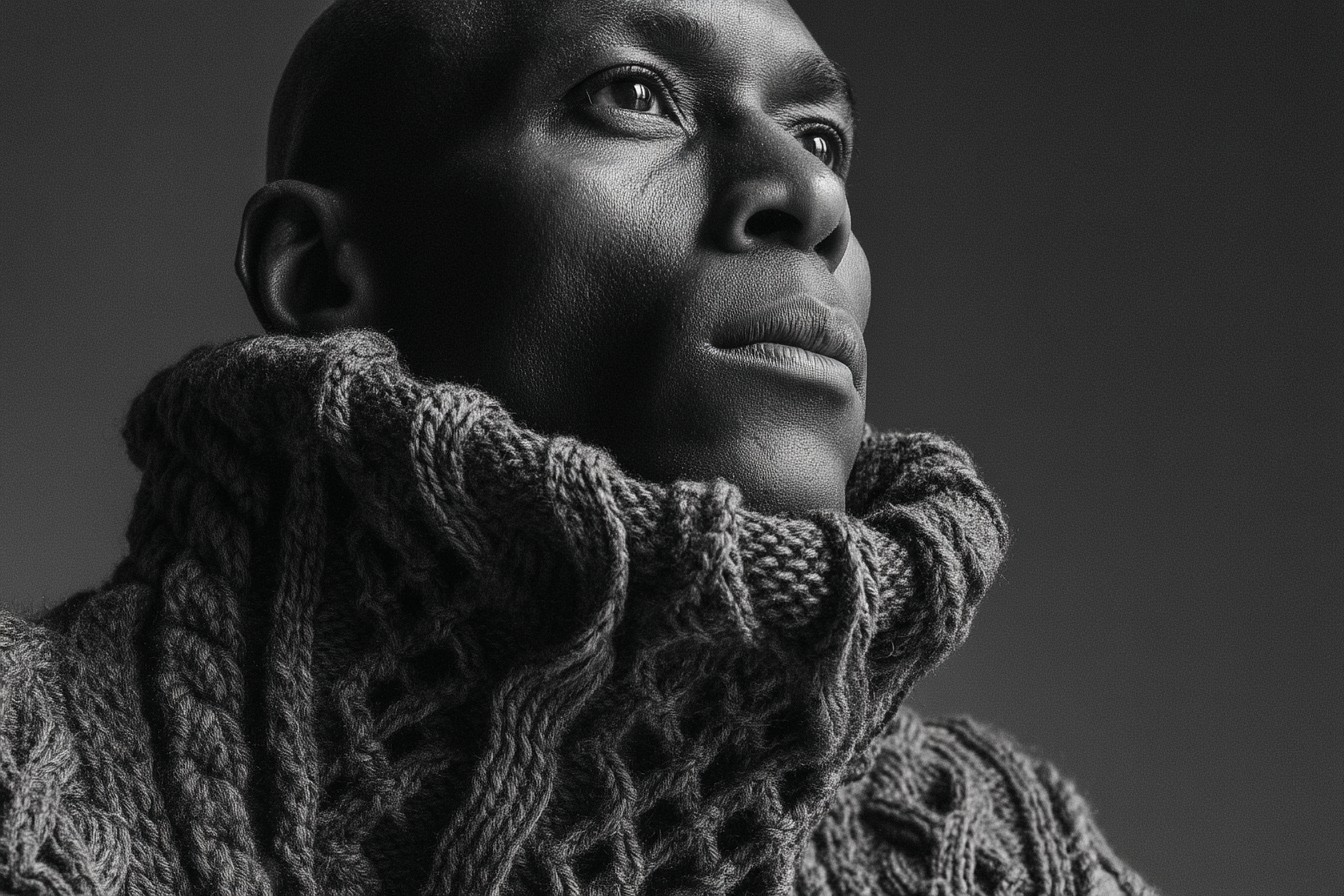

What separates their products from mass-market alternatives? It starts with the raw materials. Proper Scottish knitwear typically uses fibres like geelong lambswool (a particularly fine grade from Australia), cashmere from the best regions of Inner Mongolia, or sturdy Shetland wool from, well, the Shetland Isles. The fibre length is crucial—longer fibres create stronger, more resilient yarn that resists pilling. The yarns are often two-ply or three-ply for durability, rather than the single-ply constructions that dominate cheaper products.

I visited Lockie’s factory a few years ago for a feature I was writing. The thing that struck me wasn’t just the quality of the machines (though some were impressively vintage), but the skill of the operators. These weren’t people mindlessly overseeing automated processes; they were craftspeople making constant minute adjustments, quality checks, and decisions. Machines knit the panels, but human eyes and hands ensure those panels meet standards established generations ago.

What does this mean for the end product? Take one of Lockie’s lambswool crewnecks. The collar sits perfectly against your neck without stretching or sagging. The ribbing at cuffs and hem provides structure without creating that awful “mushroom” silhouette. The wool itself has a beautiful hand-feel—substantial but not scratchy, warm without being stifling. Most importantly, it improves with age, softening and developing character instead of deteriorating.

Another Scottish maker worth knowing is Jamieson’s of Shetland, who specializes in traditional Fair Isle patterns using wool from Shetland sheep raised on the islands. Their jumpers aren’t just garments but cultural artifacts, maintaining patterns and techniques that reflect centuries of local tradition influenced by Nordic and Scottish elements. The result is knitwear with genuine character and provenance, the antithesis of generic global fashion.

I’ve had a Jamieson’s Fair Isle crewneck for nearly a decade now. It’s my go-to for winter weekends in the country, and despite countless wears, a memorable encounter with a barbed wire fence, and being borrowed by various friends and partners, it looks virtually identical to the day I bought it. That’s the magic of proper wool and proper construction—it wants to return to its original shape, to keep doing its job regardless of how you treat it.

Moving south of the border, Johnston’s of Elgin deserves special mention. Established in 1797, they’re one of the few vertical manufacturers left in the UK, meaning they handle the entire process from raw fibre to finished garment. Their specialty is cashmere, and while their Scottish heritage is central to their identity, they now straddle the worlds of traditional knitwear and contemporary luxury fashion.

Johnston’s cashmere is among the finest I’ve encountered—dense enough to provide genuine warmth but with a softness that makes synthetic fibres feel like sandpaper by comparison. Their plain cashmere crewnecks represent the pinnacle of understated luxury—the kind of garment that doesn’t announce its quality through logos or obvious design features but reveals it through how it feels against your skin and how it drapes on your body.

For something with more obvious character, North Sea Clothing produces heavyweight jumpers inspired by those issued to Royal Navy sailors during WWII. These aren’t delicate luxury items but proper functional knitwear designed to keep you warm in genuinely challenging conditions. I have their “Submariner” model—a hefty roll-neck in undyed British wool that’s built like a bulletproof vest but remarkably comfortable once broken in. It’s the knitwear equivalent of a Land Rover Defender—not the most refined, but utterly dependable and possessed of an honest, functional charm.

John Smedley occupies a unique position in British knitwear—more refined and fashion-conscious than traditional makers but maintaining production standards that fast fashion brands couldn’t begin to approach. Their speciality is fine gauge knitwear in merino wool and Sea Island cotton, creating pieces that work as well in professional environments as casual ones. Their “Hunter” merino polo is a personal staple of mine—lightweight enough to layer under a jacket but substantial enough to hold its shape through years of wear.

Smedley’s approach represents a perfect middle ground between heritage and modernity. They honor traditional manufacturing techniques while creating designs that feel contemporary. Their pieces aren’t cheap (expect to pay £150-200 for a basic merino jumper), but like all proper knitwear, they operate on a different economic model from disposable fashion—buy once, keep forever.

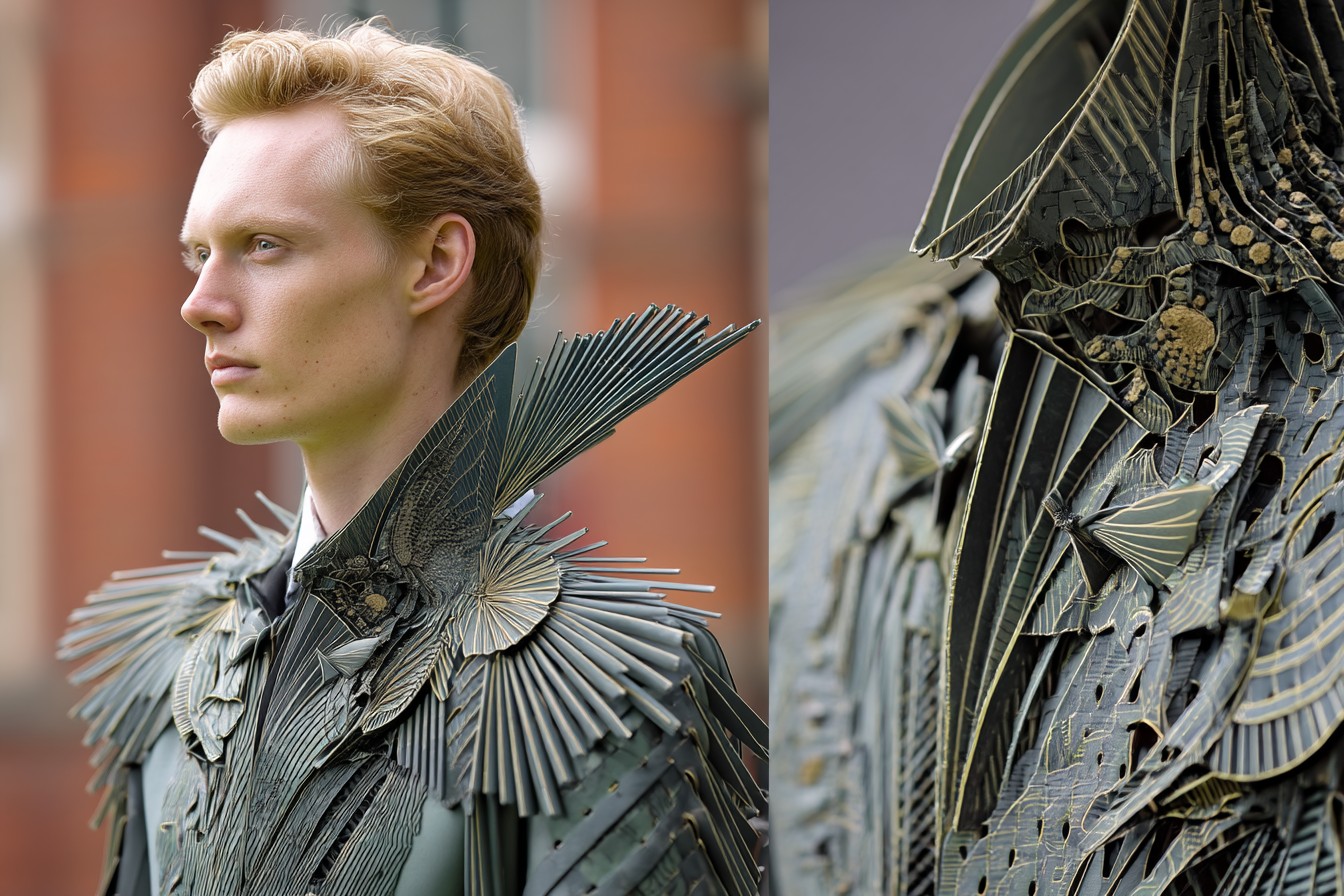

For those seeking something more design-focused but still built on traditional quality foundations, Albam creates knitwear that feels both timeless and distinctly modern. Their lambswool pieces are manufactured in the Scottish borders using traditional techniques, but the cuts and details reflect contemporary sensibilities. The combination of old-world manufacturing and thoughtful modern design creates pieces that don’t feel like costume-wear (always a risk with heritage brands) but still carry the substance of proper craftsmanship.

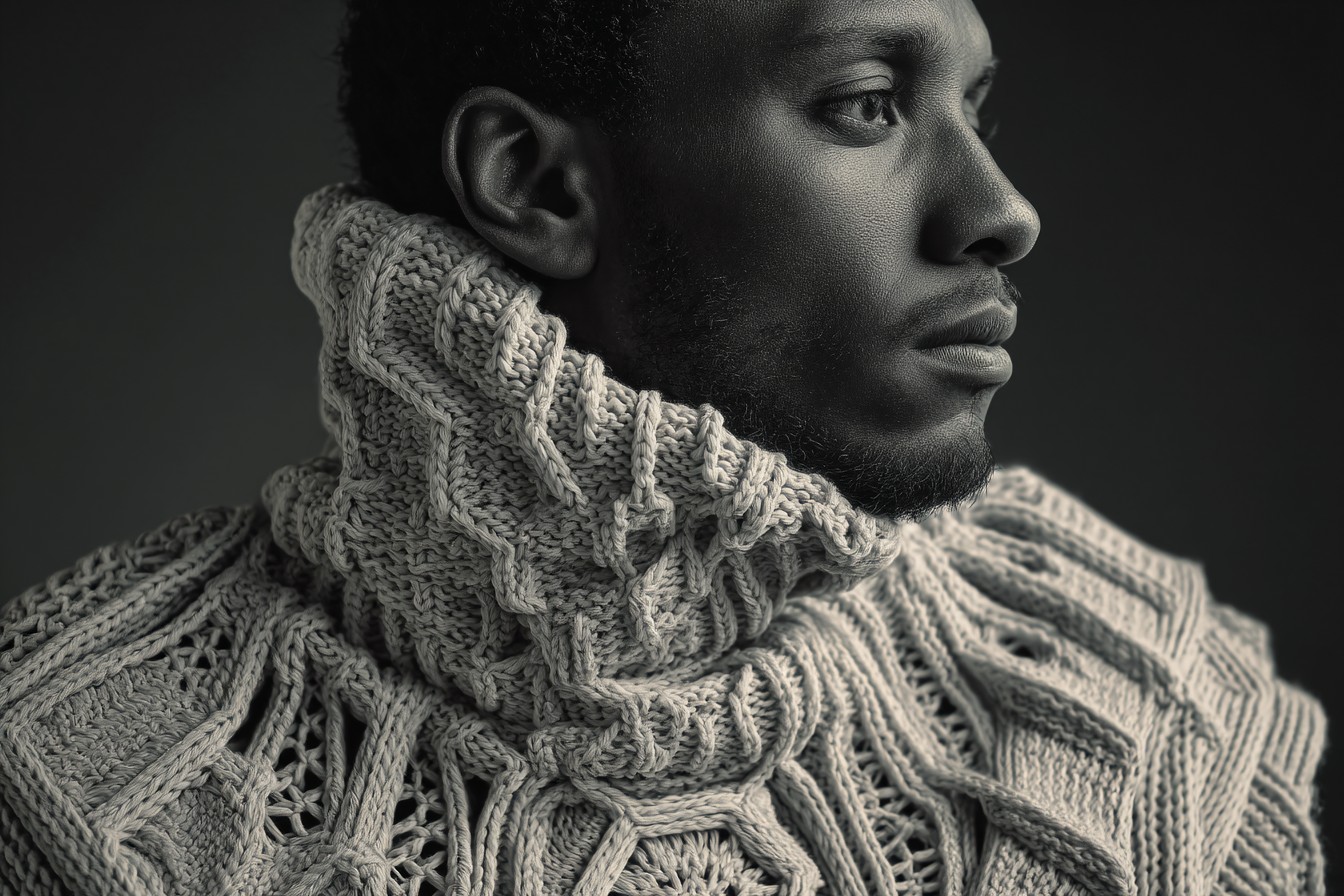

What these brands share is an understanding that knitwear isn’t just about aesthetics but performance. A properly made jumper does more than look good—it regulates your temperature, moves with your body, and improves rather than deteriorates with age. It forms a personal relationship with you, conforming to your movements and habits while maintaining its essential integrity.

Caring for quality knitwear isn’t complicated, but it does require breaking some common habits. Most importantly, good wool jumpers rarely need washing—wool is naturally antibacterial and releases odors when aired. I have some jumpers I’ve never properly washed, just aired and occasionally spot-cleaned when I’ve had an unfortunate encounter with red wine or someone else’s dinner.

When washing is necessary, cool water and gentle wool detergent is all you need—never regular laundry detergent, which will strip the natural oils from the wool. Lay flat to dry rather than hanging (which stretches the fibres) or using a tumble dryer (which can cause shrinkage and damage). A proper wooden jumper board (yes, such things exist) helps maintain shape during storage, but isn’t essential if you fold carefully.

Small holes or damage shouldn’t mean the end of a quality jumper’s life. Most of these brands offer repair services, or you can find specialist repairs through services like The Restory. I have a beloved cashmere crewneck that suffered an encounter with a friend’s new puppy—a few repair stitches later, and it’s back in regular rotation, albeit with slightly more character than before.

The joy of proper British knitwear isn’t just its longevity or performance—it’s the connection to a tradition of making that feels increasingly rare in our disposable age. When you wear a jumper from these makers, you’re not just buying a product but participating in a lineage of craftsmanship that stretches back generations.

My grandmother’s navy jumper still sits in my wardrobe, now approaching its third decade of life. I don’t wear it often—partly because I’m considerably larger than my eleven-year-old self, and partly because I want to preserve it. But every time I see it, I’m reminded of what proper making actually means—creating something with the skill, materials, and intention for it to outlive its creator. In our era of disposable everything, that feels like a radical act of defiance. As British winter approaches once again, perhaps the most sustainable choice isn’t the latest eco-marketing campaign from a fast fashion brand, but investing in a jumper made the way my grandmother would recognize—properly.